a love letter to oleg kulik

(This featured article was originally published in ArtNet magazine in 1997. It was later reproduced in a catalogue by Icon Gallery in London and subsequently translated into Russian for publication in Russia.)

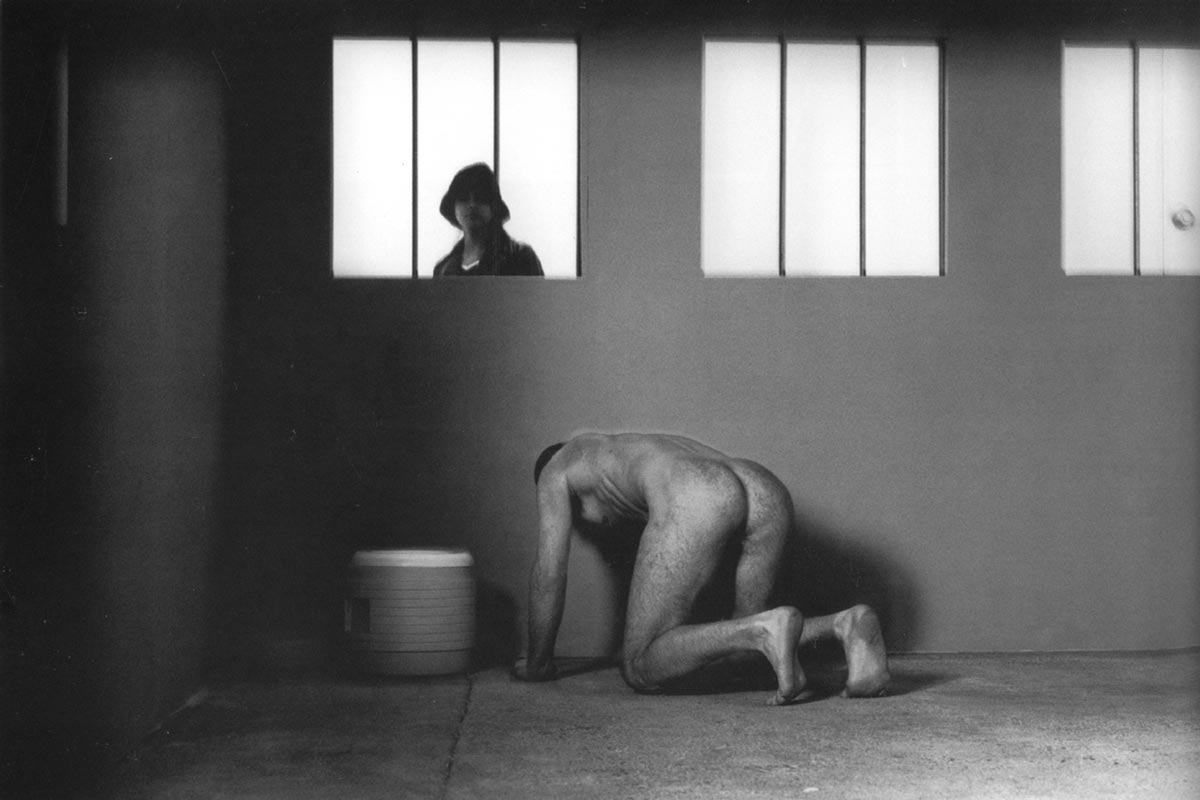

I’m standing looking into your cage, listening to the baffled and banal comments of onlookers. You want me to believe that you are a dog. You want me to believe that you believe you are a dog. But I know better. And so do you. The materials available at the front desk suggest that this performance is about animal rights. But that is not you. Not some animal rights activist who steps over homeless people sprawled across his stoop on the way to work. So, it’s not about animal rights. Maybe it’s about our animal natures. Not a metaphor for being treated as a dog. Women are treated as dogs by culture. Minorities too. But not white men. Surely, not even in Russia. Then again, maybe in another country a post-cold-war Russian male is a dog. Not to the Chase Manhattan bank in Soho, where the ATM politely asks if it is to proceed in English or Russian. Remember Ben Blue riding his horse Beatrice through the landscape of ‘60s America screaming, “The Russians are coming, the Russians are coming!” But the Russians didn’t come until the cold war was over. You didn’t come until the cold war was over. You approach the glass window and spy my book. I hold it up to the glass for you to see and you smile. And suddenly I’m smitten. In her first novel Anne Michaels says, “What is love at first sight but the response of a soul crying out with sudden regret because it realizes it has never before been recognized?” I notice that a young girl has put on a pair of heavy blue overalls and a large protective mitt. She enters your cage. She looks very sweet and very innocent. I assume, at first, that she is part of the gallery staff. She beckons you and you come to her. She is overdressed and you are naked. No dog sweaters for you. She is crouching down, offering her hand. You get very close and sniff her neck, her face. Then you move around her. You are between her and the wall. I wonder — are you licking her face? Is your tongue in her ear? Suddenly her neck bobs and she giggles. In that moment before her chin hit her chest…. I discover that anyone can enter your cage. In the time since your exhibition opened approximately ten people have chosen to do so. Foolishly, I forget to ask if they were all women although I am sure that they were. I am neither as young nor as innocent as the previous visitor. I entertain the curious conceit that you are lonely and bored. This is probably ridiculous, with all this attention you are fully entertained. I won’t know what to do with myself when I get in there. So I bring my book. I’m going to sit and read to a dog, or at least a man who wants me to treat him as though I believe that he is a dog. I should be used to this by now. My daughter is a different animal every half hour and if I am unconvinced her wrath is boundless. I couldn’t have been reading something like Russia’s Lost Literature of the Absurd. Those peculiar little stories by Danil Kharms and Alexander Vvenensky. Or Tatyana Tolstaya’s fabulous review of David Remnick’s Resurrection: The Struggle for a New Russia. I read that last week — on the subway. And by the way, I love Gorby too. No, it was Claudia Koonz’ Mothers in the Fatherland: Women, the Family and Nazi Politics. Perhaps a critical look at German culture is O.K. The trouble with Joseph Beuys was that his work always seemed to me to be continuous with and not a break from National Socialist culture. A very unpopular opinion. I didn’t want him as my leader. The gallery staff insist that you don’t speak a word of English so it shouldn’t matter what I read. Of course, I don’t believe them. So I enter your cage in the mandatory padded overalls and the oversize mitt. I bravely dispense with the mitt. You come up and take it away. A lot of angry barking. I start by crouching down against the wall by the door. The padded clothes chafe my neck. I finally manage to sit down cross-legged. I have left my glasses outside of the cage because I can’t read with them on. When you are far away you are in soft focus. When you come close I can see you clearly. I mutter the four words that I know in Russian: good afternoon, thank you, no and bird. You were a bird once. I start reading. Not at the beginning, but where I last left off. You go and lay down. There is a potty near the foot of your bed. I find myself wondering if you defecate while the audience is watching or if you wait until everyone has left the gallery. Americans always laugh at shit jokes. Next, I find myself in a conversation with a young girl standing outside of your cage who has been to the gallery previously and who has returned with a small blue ball. She has tested it by putting it into her own mouth to make sure it is not too small. When she tosses it to you she doesn’t want you to swallow it by mistake. When I entered your cage at 5 p.m. I actually thought that I would be able to sit with you for the hour that remained until the gallery closed. Only ten visitors in two weeks and now three in less than one hour. I have been reading to you intermittently. You seem to enjoy it for a time. One of the staff at the cage door tells me that someone else wishes to come in. The girl with the blue ball. Evidently, only one visitor is allowed at a time. Two women sitting in your cage might make you look too domesticated. I have to leave. As if to reinforce this message you approach barking loudly. You look threatening. The closer you get, the less I want to leave. I don’t want you to believe for one minute that I am afraid of you. When I was very young I worked in a psychiatric hospital with people who were truly mad. I’m not so easy to intimidate. You come very close. Your face is covered with sweat. Or perhaps it is just water lapped up from your bowl. Now your face is a few inches from mine and you are snarling. A dog that close — you’d feel its hot breath on your face. If you were my sister’s Doberman acting like this—I would be afraid. I don’t keep pets myself. But I would keep you. And that, it seems to me, is conclusive proof, my dear sweet Oleg, that you are not an animal, you are not man’s best friend, you are—quite simply—a man. An intellectual. Americans are notoriously anti-intellectual. I don’t share their antipathy. I know just how serious you are and so I can love you all the more. But I don’t know how to tell you—I’m not much good at barking. I’ve decided, therefore, that I am going to allow this letter to be published. I wonder, will it be “hailed” by you? Or will it float around in cyberspace forever missing its mark. It’s a dog’s life. Truly.

Love for eternity,

Susan Silas