expanded photography:

Robert C. May Photography Lecture, University of Kentucky, 2023

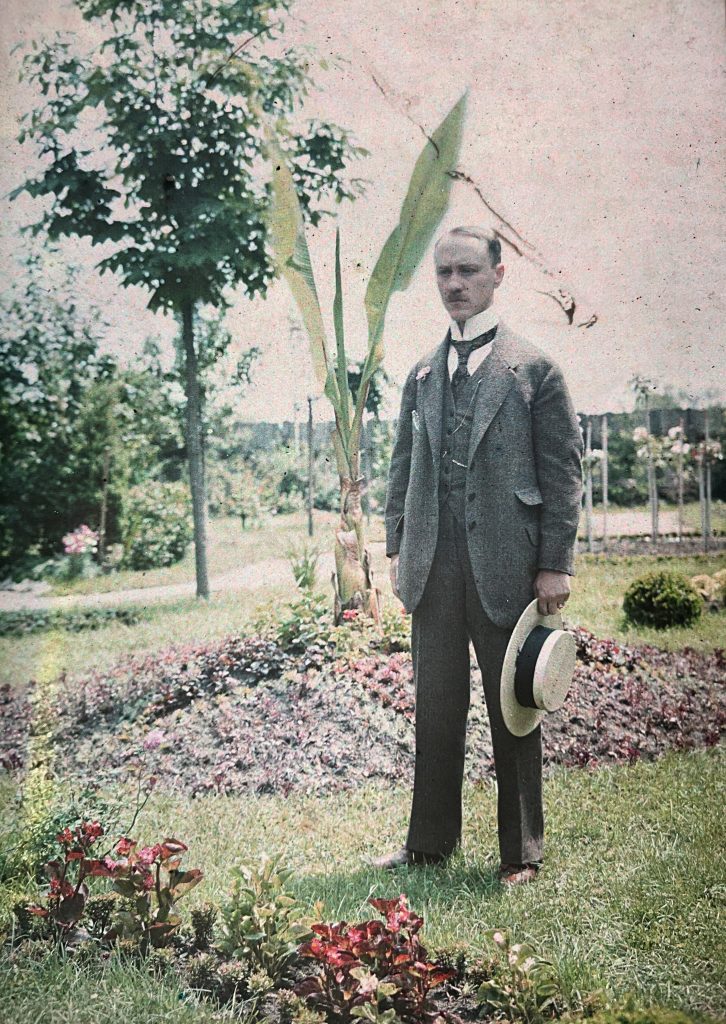

I am starting by showing you this photograph, partly for fun and because I own it. This is an autochrome or I should say—a digital photograph of one. It is a glass plate positive measuring 4.5” high x 3.5” wide. The autochrome was a short lived technology using potatoes as a substrate invented around 1905. My best guess is that this portrait was shot around 1923, making this autochrome 100 years old. It happens to be a photograph of my maternal grandfather, Czukor, Sándor.

This next image is a self-portrait. Shot in 1979, it tells you something about where the technology of photography stood around the time I began my deep engagement with it. Most photographs then were shot using black and white film and printed on silver halide paper in darkrooms using enlargers, developers and fixers. Photography back then had a smell and a certain kind of alchemical magic as images slowly arose in the reddened darkness of a safe light inside a developer tray. Despite the efforts of Alfred Stieglitz earlier in the century, and even though a serious survey called The History of Photography from 1839 to the present day by Beaumont Newhall had been published under the auspices of the Museum of Modern Art as early as 1949, one in which all of the reproductions appear in black and white, photography was still engaged in a genuine struggle to find legitimacy as fine art when I began making photographs in the mid 70s. In fact, the conception of a unique history of photography in isolation from other art forms contributed to the problem. It is only in the recent rehanging of its collection in its new home, which opened to the public in 2015, that The Whitney Museum finally exhibited photography as a full fledged medium integrated with painting and sculpture and drawing rather than segregating it off entirely on its own.

What do I mean by the title expanded photography and what is my subject matter? How do an evolving form and intentional content unfold together? By expanded photography, I mean the entire realm of possibilities opened up when photography moved from an analogue to a digital technology, creating new languages I could use to speak about embodiment.

I came to my subject matter as a young child, even though I wasn’t conscious of it for some time. My parents were Holocaust survivors, Hungarian Jews who immigrated to the United States in 1949, the same year Beaumont Newhall published his book. My childhood imagination was peopled by images that I never remember seeing for the first time. Black and white images of desiccated bodies stacked in piles or being bulldozed into giant pits full of lye.

In 2011, I came across an extraordinary exchange that gave me a new vocabulary for what those bodies had represented for me and a clearer understanding of how they had insinuated themselves into my psyche and work. In an article by Saul Bellow in the New York Review of Books he quoted a passage from Lionel Abel’s memoir The Intellectual Follies:

But I had no real revelation of what had occurred until sometime in 1946, more than a year after the German surrender, when I took my mother to a motion picture and we saw in a newsreel some details of the entrance of the American army into the concentration camp at Buchenwald. We witnessed the discovery of the mounds of dead bodies, the emaciated, wasted, but still living prisoners who were now being liberated, and of the various means of extermination in the camp, the various gallows, and also the buildings where gas was employed to kill the Nazis’ victims en masse. It was an unforgettable sight on the screen, but as remarkable was what my mother said to me when we left the theatre: She said, “I don’t think the Jews can ever get over the disgrace of this.” 1

The words of Lionel Abel’s mother caused an instant shudder of recognition—underlying my work was this internalized conception of the disgraced Jewish body and it had always been there. The impulse to photograph myself, the obsession with classicism and beauty, the attempts at recuperation using images of dead birds were all tied to those corpses. It may also explain why I have a commitment to live capture, and despite the expansion of photography into the digital and virtual, why my work, even when it meanders into the space of 0s and 1s, always returns to the material, occupying lived space and demanding an accounting from it.

At the point in the history of photography when those black and white photographs that so profoundly influenced my development as an artist were taken at the end of World War II, there was a consensus that the photograph functioned much in the way that Roland Barthes described in Camera Lucida. According to Barthes, “Every photograph is a certificate of presence.” 2 Barthes was concerned both with the indexicality of the photograph, e.g. what it referred to—generally the moment when the light reflected off the subject created an impression on the negative, and with the iconicity of the photograph, e.g. what that person or thing being photographed looked like. For him the photograph was simultaneously a record of embodiment and of disembodiment, or a moment forever lost and irretrievable. I would describe this entangled relationship of embodiment and disembodiment both as an aspect of the technology and an aspect of the content of my work. Barthes says: “This will be and this has been; I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is at stake. In front of a photograph of my mother as a child, I tell myself: she is going to die: I shudder, like Winnicott’s psychotic patient, over a catastrophe which has already occurred. Whether or not the subject is already dead, every photograph is this catastrophe.“3 In the unspeakable present of the Holocaust images that brought me to my subject matter, present and future collapse —for what anterior future could they have?

Despite the advancements made in the technologies of representation, live capture, whether made with a digital camera, laser scanning or photogrammetry, retains its iconicity. In other words, the process still records something captured in real space that will resemble the thing captured. But indexicality has changed. As the scholar Kris Belden-Adams remarks in an article titled, Don’t Hate the Index: Reconsidering the Promise of Pierce, the index has become “slippery” 4 and we are no longer sure exactly which moment in a chain of digital incarnations it refers to. It is here, in the realm of the index that photography has expanded in unexpected ways and allowed for a strange circuitry of impressions from which the material manifestations of a live capture can take on new and different forms. In addition to a more traditional photograph or video, my work can now be output as a wireframe drawing, a motion capture video, a 2D rendering of a three dimensional object, a 3D model, a glass sculpture, a marble sculpture or a bronze sculpture, to name a few.

based on an early 3D model of the Covid 19 virus

crystal 48% lead glass

I do not believe that content is separable from form anymore than I believe that the mind can be separated from the body. Form is akin to our skin, it determines an outside boundary and delineates what is inside—the limits of the container and what it can express. As the technology of photography advanced, it subtly effected the content it housed. By the time I created the series, EYES WIDE SHUT, in 2010, documenting the decay of a Cooper’s Hawk, I was shooting everything with a digital camera. This meant the ability to see each image as it was shot and make adjustments as I went along. Because the work was time based and recording actual decay, the digital technology eliminated the need to wait for negatives to be developed, by which time the bird would have changed and adjustments would not have recorded the same phase of decay.

I was not aware when I began photographing these dead birds that my images were related to the work I had done on the Holocaust. Somehow these small embodied creatures had unwittingly become a substitute for those images I had seen as a child; bodies that were the ultimate disembodiment, because they no longer represented individual beings and because they depicted bodies that had gradually eaten themselves alive, disappearing from within until they could no longer exist. What remained of each was a flattened leather-like husk.

Retrospectively, I can also see that these dead and decaying birds were not merely stand-ins for the corpses of those victims, they were also an attempt to give some kind of dignity to those desecrated bodies; a perverse transubstantiation, through which degradation is morphed into beauty, attempting to intervene after the fact, in the systematic process of what Primo Levi described as the creation of “miserable and sordid puppets,”5 because the shame of this demotion to something less than human haunted those bodies, those disgraced bodies, even in death.

My first marble sculpture was the culmination of a body of work titled, the self-portrait sessions. The foundation of this portrait series was built on mirroring (I literally sat in front of the mirror gazing at my own reflection and the image was constrained to this mirrored space—the mirror’s edges are never seen). The photographs themselves were indexical but they also adhered to an internal logic of indexicality (e.g. the image of the self outside the mirror pointing to the self inside and vice versa). The images were also iconic (e.g. depicting verisimilitude to me).

As the photographs accumulated over the course of a decade, I began to notice myself aging. The images I shot in the mirror were sharper either in the foreground space or in the mirror, due to a limitation of camera lenses called depth of field, and I began to see the softer self, which appeared less wrinkled and less flawed, as my idealized self. This suggested the idea of creating a representation of an idealized older body. The Western tradition of marble sculpture is not only limited with respect to diversity it also limited with respect to the representation of aged female bodies. A new technology existed through which I could create what was essentially a 3D photograph of myself. Ironically, marble seemed especially suitable because inherent in the material is an idealizing or smoothing of flaws that is part of the process of polishing.

white Sivec marble

AGING VENUS, is a contemporary iteration of classical sculpture using my aging body as a model. The preparation for this sculpture began with a 3D scan of my body, realized by photographing me on a small stage surrounded by cameras (called photogrammetry), and then stitching the individual photographic fragments together to make a 3D object file. The sculpture was cut from white Sivec marble by a high performance 7-axis robot. In order for the robot to cut the marble, the object file is programmed into new software that the robot recognizes as the model to be carved. This process, while completely data driven, does retain a ghost of the index, that moment when I stood in the photogrammetry booth, and the data is reverse engineered back into a material likeness of me that we can easily recognize.

As talk of Whole Brain Emulation, or WBE, gained steam, I began thinking about the men who were so ready to ditch their bodies in the belief that they could achieve immortality by uploading their minds onto an inorganic substrate. My sculptures, AVATAR, 2021 and Avatar Bending Forward, 2021 are polished white bronze sculptures made in my likeness and inspired by imagining a suitable container for my own brain upload. In my motion capture video EULOGY, 2020, which was produced before the two sculptures, my avatar narrates its observations about being that brain upload.

polished white bronze

I am always brought up short when I think I am about to say something that sounds like biological essentialism, but I can’t help but wonder if so many men are willing to discount their bodies precisely because their bodies have not been demarcated for observation in the same ways as the bodies of women, minorities and even animals. Perhaps that gives their bodies a false sense of weightlessness that everyone else categorized as other does not experience. The weight of embodiment is perfectly described by J. M. Coetzee in The Lives of Animals: “To thinking, cogitation, I oppose fullness, embodiedness, the sensation of being — not a consciousness of yourself as a kind of ghostly reasoning machine thinking thoughts, but on the contrary the sensation — a heavily affective sensation — of being a body with limbs that have extension in space, of being alive to the world.”6

I have thought a lot about embodiment, in relation to aging, and in relation to the social and psychological consequences of being marked by gender. I already stated that I don’t believe that the mind and the body can be separated. As the modernist mind/body dichotomy and the male/female dichotomy (this one with far more resistance and backlash) disintegrate, aided by the fluidity of the digital, it becomes easier to create a seamless representation of a hybrid body. If the images are constructed from live capture they will also retain both their indexicality and an obvious iconic value or likeness.

Two of my works, one a study for a sculpture and the other an existing white bronze sculpture, marry together my husband’s body and mine. In the first, Ode to Echo and Narcissus, we are joined together on the vertical just above the groin in a figure based on a Roman antiquity called the Mazarin Hermaphrodite housed at the Louvre. In the second, the work is constructed by combining a scan of my head with that of my husband’s, suturing our heads together on the vertical between our eyes. This sculpture, cast in white bronze, is both a personal and speculative imagining of our avatar in a world in which our brains have been uploaded into the same data container. This is the shell in which we are reborn as a data set for eternity. In my motion capture video HYBRID that speculation is spun out in 10 short animated vignettes.

white bronze

stills from a 4k motion capture video

Currently, there are works of contemporary art created from whole cloth inside the computer and entirely independent of “real” space. Some are quite compelling. For images created inside the computer the notion of indexicality is irrelevant—that moment in real time in which an impression from lived space is transformed into representation. My work makes a commitment to lived space through a process of live capture and a return to that space by virtue of the creation of a material object that can only live there. The same impulse to reject the binary and its enforced limitations, the Descartes, Hegels, etc. and to side with the materialists, Stoics, Spinozas etc. ends up being both a philosophical inclination, with all its political implications and an artistic decision about process and materials. The commitment to sculpture especially, is a commitment to the physical world. It is fashionable to express doubt and skepticism about the existence of the “real” world. Apart from my own intuitions, the most cogent comment I have ever read in response was in Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses: “The world, somebody wrote, is the place we prove real by dying in it.”7

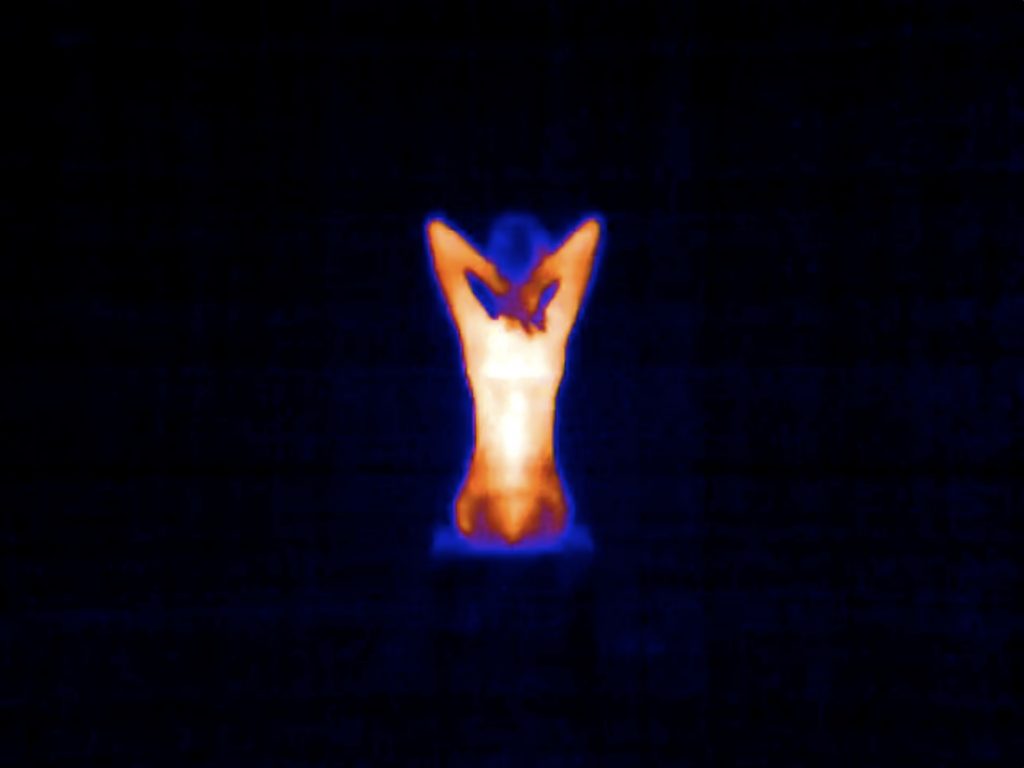

Photographs and video works also affirm a commitment to the “real” world. The photographic series love in the ruins; sex over 50, an intermittent documentation of the resilience of two aging bodies and the video work there is no time without heat, shot with a thermal camera that literally records the heat generated by a living body, both speak to the imperative of lived space, reflecting the inevitable problem of occupying it—that of entropy and thus mortality.

Filming in the open landscape of Cody, Wyoming with a falcon inspired my most recent series of sculptural works titled natural history. Working with a wild raptor was a profound experience. In John Berger’s beautiful essay, Why Look at Animals? written in 1977, he says that consumer societies broke down established traditions that existed between man and nature, traditions that recognised that “animals were with man at the center of his world.” Berger traces a shift in man’s relationship to animals, one in which the exchange of the gaze between them disappears. “In the accompanying ideology, animals are always the observed. The fact that they can observe us has lost all significance. They are objects of our ever-extending knowledge.” 8 The creation of observed classes of beings is about denying their agency and it has contributed to the current level of disastrous extinctions of birds and animals, not to mention the battle over who owns women’s wombs. My three channel video, the woman and the falcon, 2022, is an attempt to explore a recuperation of the exchange of the gaze between human and animal.

While working with the falcon I became aware that we both live in this world as part of an observed class. The gaze that entraps women and the one that ensnares animals is not the same, yet we share a form of embodiment that is forcefully relegated to the role of the observed—a gaze that limits exchange in order to attain mastery and exert power. Thinking about the shared effects of this unwanted paradigm has led me to a new body of work constructing hybrid forms which conjoin the remains of animals and my own body—a way of thinking our materiality and our interdependence.

These works are part of that thinking:

life size statuario marble

tombasil (white bronze)

model for a bronze sculpture currently being cast

- Saul Bellow, “A Jewish Writer in America,” The New York Review, 10 November, 2011

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Hill and Wang, 1980, 87

- ibid, 96

- Kris Belden-Adams, Don’t Hate the Index: Reconsidering the Promise of Pierce, Afterimage vol 39, 2012

- Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz, Simon and Schuster, 1996, 26

- Coetzee, J.M. The Lives of Animals, Princeton University Press, 1999, 33

- Salman Rushdie, The Satanic Verses, Viking, 1988

- John Berger, “Why Look at Animals,” About Looking, Vintage International, 1980, 16