Linn Underhill: Analogue Body Extraordinaire

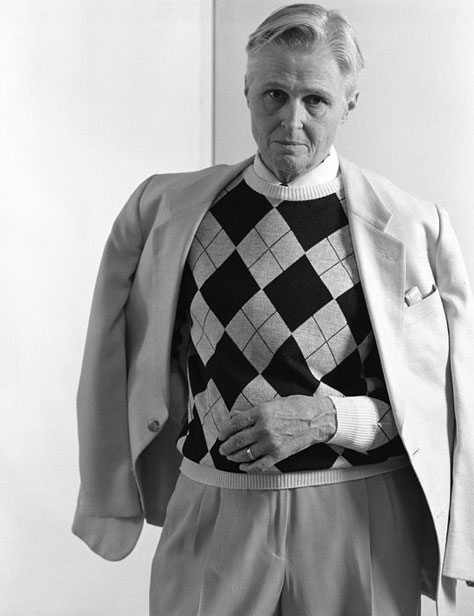

In 1998, at the age of sixty-two, the photographer Linn Underhill made a series of black & white self-portraits titled NoMan’s Land, in which she performed the male subjects in photographs taken by George Platt Lynes (1907-1955). She is wholly conscious, in her photographs, of the adoration with which Lynes’s camera lens caresses his subjects. She understands and addresses the construction of glamour those photographs were engaged in—the willing participation in the process of Lynes’s beautiful young male models and celebrity subjects.

A peculiar inversion happens when she inhabits this space. It is not merely the matter of gender reversal but something more complicated happening in the relay of the gaze. In most of the images her gaze directly confronts the viewer, because she is looking directly into the camera lens, which is at the same time a gaze directed at the artist, in other words back at herself, and yet her camera insinuates the gaze of Platt Lynes standing behind the camera creating those eroticized images of men back in the 40s. There has been fairly extensive theoretical discussion of female identity as masquerade. Here, Underhill allows the acknowledgment of envy—the envy of male privilege, while at the same time exhibiting real empathy and connection to the subjects she has chosen to reincarnate.

Seventeen years later, Underhill has produced another body of self-portraiture. In these photos, the artist appears to us standing on a neutral but warm seamless backdrop, with a few assorted props, but essentially naked. With the exception of the artist holding her cat in her arms, the photographs are short sequences of from three to six images. We see the artist crying, we see her in work boots, splitting a log with an axe, we see her heft a cape into the air and wrap herself in it, we see her jump up in the air, we see her put on sweat pants and a sweat shirt. In all of these images she is engaged with the camera and by inference with us, her audience. She is steadfast, fully present and unselfconscious.

What does it mean to inhabit the body so ferociously at nearly eighty? There is an element of joy to these images. The declaration: “Look here, I can still do all of this. Isn’t that remarkable?” We see an honest depiction of an aging female body, something we see very little of in popular culture. We rarely see fully mature adults having sex in films, let alone see the bodies of eighty year old women naked in film, on television or in magazines. One response to the rare images of older women, naked or not, that I have personally heard is: “Who would want to look at that?” I would contend that we are all, within a certain subjective range, hardwired to be attracted to beauty, but we know so little of the older naked body that we haven’t even had the chance to make an assessment. I also can’t help but wonder if John Coplans heard this response to the images of his old, naked, male body, or if this response is reserved solely for women. I don’t know the answer to that question.

At a moment when the discussion of shedding our bodies entirely, as discussed, for example, in a recent New Yorker article (The Doomsday Invention: Will artificial intelligence bring us utopia or destruction? November 23, 2015) no longer seems beyond the realm of possibility, what does it mean to live in an analogue body and to reach a certain age living inside that slowly decaying form?

I recently learned that in discussions of virtual reality, artificial intelligence and potential bodilessness, the space our flesh bodies inhabit is referred to as “meat space.” Several years ago I heard a meditation instructor claim that the body was the unconscious. He then repeated himself saying: “I don’t mean that the body is where the unconscious resides, I mean the body is the unconscious.” I was struck by that assertion and I have thought about it often since then. Let’s suppose that there is something to this idea that the body is the unconscious, and even if there isn’t—what will it mean to live outside the sensate body, if our minds can be uploaded to a computer? Is creativity already some kind of binary function? Does it depend on having a physical body or not? Some people still deny the existence of the unconscious. They prefer to see the world as seamless and aren’t interested in the fractious chaos erupting from beneath the surface. But most of us take the notion of the unconscious for granted. If the unconscious is the body, this element would be missing from our uploaded brains. It would vindicate those non-believers and make Sigmund Freud seem quaint indeed. This seems like the perfect moment to look at the aging body, the body from which all of American culture is on the run in its endless quest for the fountain of youth and immortality.

In a culture where every variety of violence and erotic fantasy is available somewhere, it is remarkable how little we see of the aging female form. The youthful female body is ubiquitous. It is used endlessly to suggest that sexual availability and eros emmanate from cold beer cans, fast automobiles, even pizzas. It is with great confidence that this youthful Madison Avenue body is deployed to manipulate male desire and at the same time create an insidious form of despair in the female unable to match its perfection and desirability (almost as if this generic model body were already an avatar), hopefully prompting in the saddened viewer a rash of comsumer oriented triage to make up for this lack. One suspects that one reason, aside from lack of interest in the male spectator, that there are less images of the older female body is that the older female is no longer so suseptible to such persuasion. After a certain age, relieved of constant cultural objectification and past child-bearing age, and considered useless from the male vantage point, women find a new kind of power and freedom. It is commonplace to hear women over sixty talk about reaching a point where they feel truly themselves, unhindered by the expectations of others. Real freedom consists in genuinely not caring what other people think. For women, this is a much more radical proposition than it is for men, as they are trained by the culture to always take account of others and their feelings.

The social contract for women is always tied to a certain form of approval from men. This attitude is so pervasive that when women make it clear that they don’t seek male approval or prefer the company of women, they are often met with hostility, threats and even violence. Linn Underhill inhabits her aging body with determination and grace and yet she exhibits the kind of freedom many women long for. A freedom from male judgement, a freedom to be true to herself, and the freedom of not caring what anyone else thinks—not in the form of an affront, but as a simple fact. In her earlier series NoMan’s Land, one senses the complicated relationship of female assertion in relation to male privilege and power. But now that binary tension between female liberty and male authority seems to have disappeared. So in fact, maybe it is not only the exurberance of still being here and still being able to jump, and cry and split wood with an axe that we see. Maybe it’s also the depiction of freedom that makes these images so compelling and joyous to behold.