“We are all witnesses”: Susan Silas’s Helmbrechts walk

by Erin Hanas

Helmbrechts walk

On April 13, 1998, contemporary American-Hungarian artist Susan Silas [b. 1953] embarked on a twenty-two day, 225-mile long journey, retracing a 1945 death march from Helmbrechts, Germany to Prachatice, Czech Republic.2 Helmbrechts was the site of an all-women’s work camp, founded in the summer of 1944 and located close to Germany’s border with the former Czechoslovakia. Camp guards evacuated all of the approximately 600 prisoners in April 1945. The Jews and their guards had to travel by foot all the way to Prachatice; the non-Jewish prisoners were left behind after seven days. Some ninety-five women died on the way, most from starvation and exhaustion, others from being shot.3 Today the site of the former Helmbrechts camp is a housing development.4

For her work, Silas compared contemporary maps of Germany and the Czech Republic with maps from 1945 in order to follow as accurately as possible the original route as described by former camp commander Alois Dörr and witnesses who testified at Dörr’s 1969 trial in Germany.5 While walking to Prachatice, she took photographs of the landscape and kept a written record of her thoughts and experiences. She then filmed the reverse trip in slow motion without sound from a car.6 Upon returning to New York, Silas compiled forty-eight of the photographs into a limited edition, unbound artist’s book. She later created an electronic version, which provides the basis for this essay.7 A pair of photographs and two short texts visually represent each of the twenty-two days of Silas’s endeavor. One caption is a journal entry from the corresponding day’s walk; the other is a news event that appeared in The New York Times on the same date. The portfolio closes with a self-portrait of the artist, an epilogue, and a map. The video has never been shown in public.8

Silas titled her work Helmbrechts walk, 1998–2003, to emphasize the difference between her personal decision to retrace the historic death march and the prisoners’ lack of agency as they suffered under the punishing eyes and actions of the camp commanders in 1945. As the term “walk” suggests, free will initiates such an event, whereas “march” connotes military compliance. The disparity of agency and the temporal disjuncture of Silas’s re-creation point to her identity as the daughter of Hungarian Jewish survivors and as an inheritor of, and secondary witness to, the trauma of the Holocaust. Her Helmbrechts walk draws attention to a central conundrum faced by multi-generations which inherit this history, as does Silas: namely, the impossibility of firsthand experience of the actual traumatic events.9 Silas expressed this perceptual gap as “a monumental failure of the imagination,” because “even being in the space where these women suffered did not make it possible to grasp the nature of what they went through.”10

The inability to know factually what occurred is particularly amplified in the case of the Holocaust, which psychiatrist and concentration camp survivor Dori Laub has described as “an event without a witness.”11 According to Laub, “Not only, in effect, did the Nazis try to exterminate the physical witnesses of their crime; but the inherently incomprehensible and deceptive psychological structure of the event precluded its own witnessing, even by its very victims.”12 Helmbrechts walk represents Silas’s effort to counter this absence by becoming a witness. As she stated: “The art work was my physical presence there— what was important with respect to the marchers and my feelings about them was putting my body in that physical space—the images are a tertiary witness to that act. My occupying space and time I wouldn’t have occupied had they not been there before me—that was most significant.”13 In short, by walking, as well as visually and textually documenting her surroundings, encounters, and feelings, Silas attempted to grasp more directly what those who marched before her experienced. She also performed the dual roles of one who testifies, as well as witnesses, albeit both belatedly, to the original victims’ suffering and deaths. The photographs, video, and personal reflections provide evidence of these processes. Moreover, the juxtaposition of Silas’s written meditations with the “cold facts” of the news reports creates another layer that demonstrates how, to quote Silas, “human agency is both restricted and shaped by historical forces.”14

Helmbrechts walk can be analysed in two parts. First, in the context of Silas’s artist’s book on the walk, which comprises selected photographs, journal entries, and news stories augmenting consideration of how the public witnesses the continual perpetration of violence and murder today. In the book, Silas includes anonymous landscape images, devoid of people, that are neither nationally nor ethnically inscribed. Thus, her artist’s book is like a highly structured, yet empty, container to be filled and completed by viewers’ reflections, which are sparked by Silas’s photographs and/or accompanying texts. As I shall note below, this notion of viewers completing the work, itself presented as an empty container, has historical precedents. Second, Silas’s work can be examined in the context of her physical and emotional engagement with the project and how that personal involvement relates her art to a history of conceptual and performance-based art, especially grounded in 1970s sociological art practices that considered identity in the context of the construction of memory, history of place, and the media. Following these two points, I discuss the conceptual and performative aspects of how Silas conjured the intrusion of past trauma in the present; describe the difference between firsthand 1945 experiences and her latter inherited secondary trauma and witnessing; consider how as an artist’s book Helmbrechts walk challenges the public by highlighting the continued existence of atrocities today; and finally place Silas’ project in the context of its art historical antecedents before drawing my conclusions.

The Journey

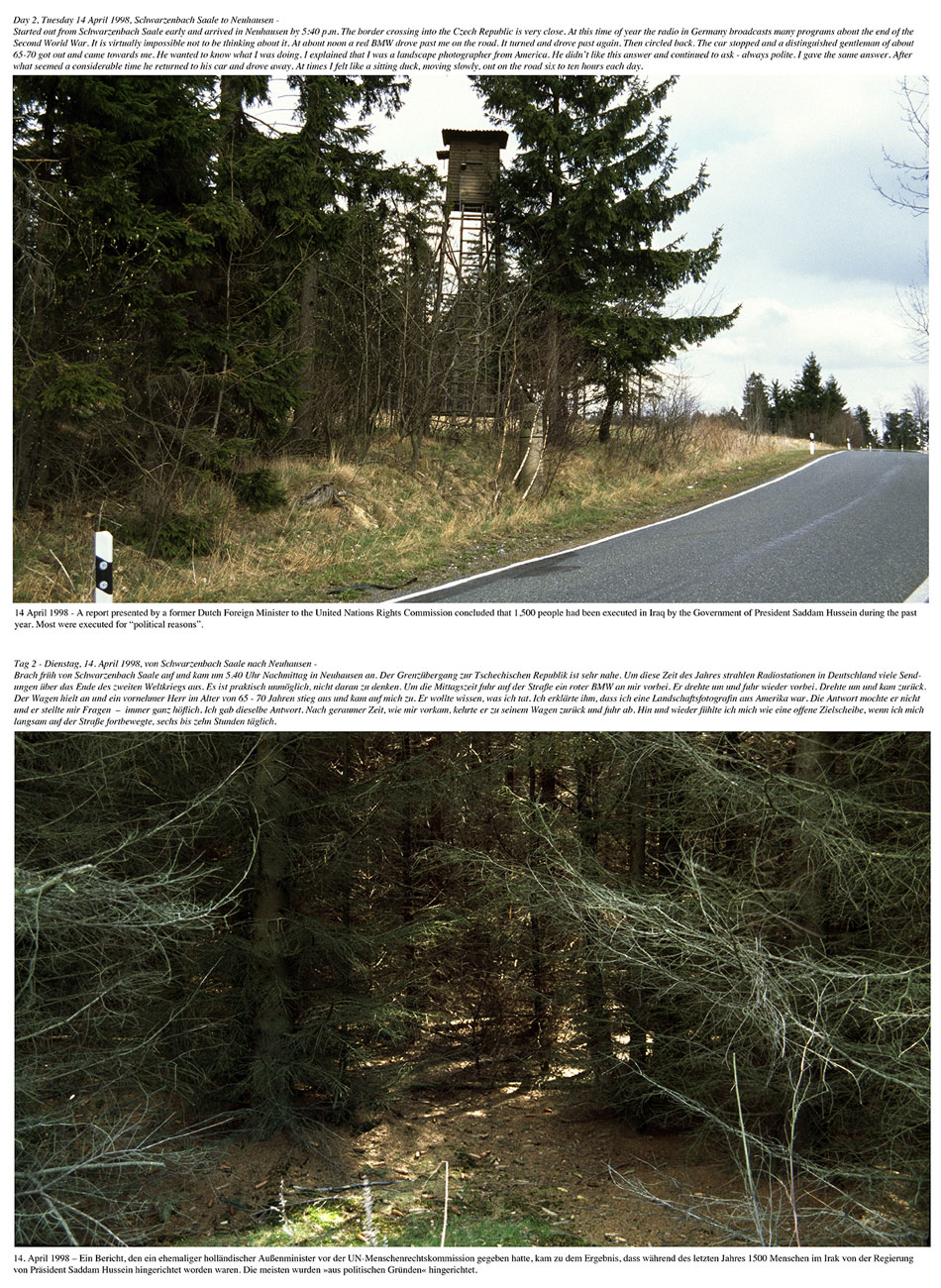

On the second day of her walk, Silas travelled from Schwarzenbach Saale to Neuhausen, Germany. She walked from early morning to 5:40 P.M. According to Silas’s accompanying text, at one point during the day, a BMW drove past, circled back, and an old man emerged to confront her, repeatedly inquiring as to her activity.

Fig. 1: Susan Silas,

“Day 2,” Helmbrechts walk, 1998-2003

Not satisfied with Silas’s insistence that she was a landscape photographer from the United States, the man eventually left. “At times I felt like a sitting duck, moving slowly, out on the road six to ten hours each day,” Silas wrote.15 Neither of the two photographs that visually represent this day depicts this personal encounter or Silas walking on the road. (Fig. 1) In the left image, barren tree branches swoop upwards to frame the densely packed evergreens in the background. The treetops are not visible. The right image shows an empty, paved, tree-lined road with a small wooden watchtower rising up amongst the tree trunks against a clouded sky. The overall feeling is one of melancholy.

The absence of people and cars in these two photographs is striking, given Silas’s disagreeable encounter with the man in the BMW and the importance she placed on her physical presence in the landscape. Art historian Brett Ashley Kaplan has analysed how the empty landscapes of Helmbrechts walk “function as a site to read violence and to resist amnesia.”16 Silas herself has described how the “landscape endured in a weird way as a witness.”17 Indeed, the landscape is all that remains of the 1945 Helmbrechts death march that Silas retraced and witnessed in 1998. Yet, her own invisibility in the photographic compositions contrasts with her written description of asserting her right as a Jewish woman of Hungarian descent to exist in the space where, fifty-three years earlier, she would have been an anonymous victim of the Nazis’ forced march. Such layering allows Silas to insert herself as a victim into the historic narrative of the Holocaust, while simultaneously maintaining independent, generational agency from it.

Thus, Helmbrechts walk relates to, but also represents, a step beyond Silas’s 1990 photomontage, We’re Not Out of the Woods Yet. In this work, she created a life-size replica of Margaret Bourke-White’s renowned photograph of prisoners liberated at Buchenwald, and placed the image upright in a forest, cut out a hole for her own head, and re-photographed the original image with her own face taking the place of that of a prisoner. Silas juxtaposed this altered photograph with an image from German artist Anselm Kiefer’s 1969 Occupations series in which Kiefer dressed in paramilitary attire and performed a Sieg Heil-like gesture in various public locations in France, Italy, Switzerland, and in the privacy of his Düsseldorf apartment.18 We’re Not Out of the Woods Yet related to Fascism, the Holocaust, and Silas’s second-generation survivor identity, through interaction with an extant photograph, whereas in Helmbrechts walk she confronted the physical space more aggressively in being in the landscape where the Shoah actually occurred.

Fig. 2: Susan Silas,

“Day 6,” Helmbrechts walk, 1998-2003

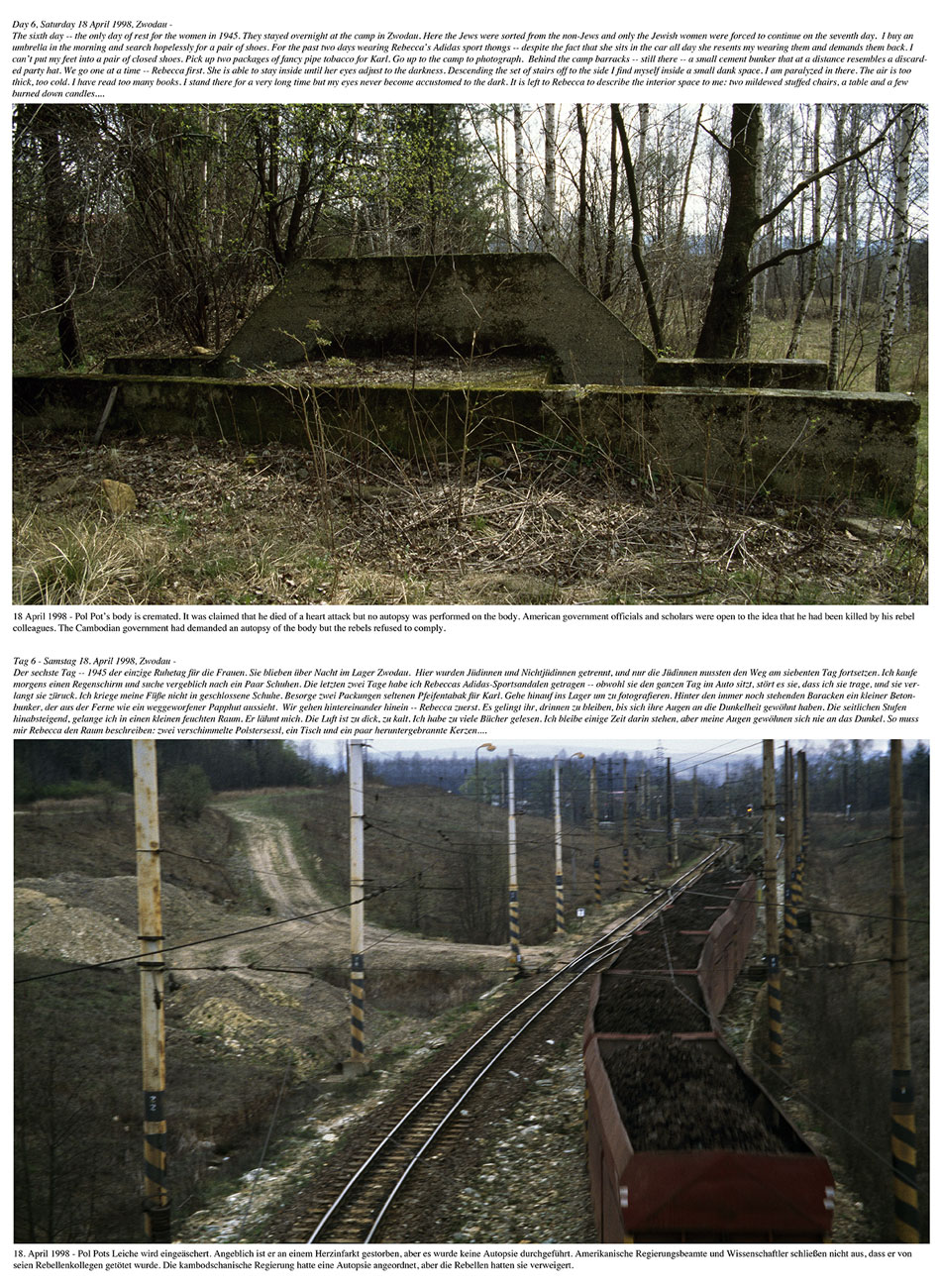

On the sixth day of her journey, the only day of rest for the prisoners in 1945, Silas rested in the town of Zwodau. Her photographs for this day depict train cars filled with coal in the middle of a desolate landscape and a World War II-era concrete bunker, darkened with moss, surrounded by trees and weeds, and located near the site of a former concentration camp (Fig. 2, left and right image, respectively). The latter photograph is a visual record of an architectural structure that witnessed to the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust.

Significantly, the bunker also brought Silas closer to tangibly experiencing the subject position of a trauma victim. Writing about her descent into the bunker, Silas stated: “I am paralyzed in there. The air is too thick, too cold. I have read too many books. I stand there for a very long time but my eyes never become accustomed to the dark. It is left to Rebecca to describe the interior space to me: two mildewed stuffed chairs, a table and a few burned down candles . . .”19 The physical space triggered the intrusion of traumatic memories conveyed to Silas through her family and her research, second-hand memories that were not her own yet none other than her own. Silas’s inability to see inside the bunker was the result of a fundamental psychological survival mechanism: the shutting off of consciousness and the process of dissociation that permits the trauma victim to continue living despite such memories and experiences. Being in the bunker initiated a more direct encounter with the originating traumatic event, such that Silas was unable consciously to witness it fully at the moment of her experience, remembering only her bodily sensation of paralysis.20 Her visual descent into darkness is a metaphor for the black

Fig. 3: Susan Silas,

“Self-portrait and Epilogue,” Helmbrechts walk, 1998-2003

hole that forms when the body literally preserves a memory of the traumatic event while simultaneously, and paradoxically, dissociating from it, leaving a void that may never entirely be recovered, if at all.21 The photograph of the bunker’s exterior and Silas’s written meditation thus function as witnesses to her slippage into the subject position of a victim. Silas’s experiences in Zwodau, however, should not be conflated with those of the female marchers in 1945. For an unbridgeable gap remains between her art and the actual Helmbrechts death march.

The disparity between 1945 and 1998 is clearly visible in the final photograph of the Helmbrechts walk portfolio. (Fig. 3) In this image, which was taken on the twelfth day of Silas’s journey, a circular roadside mirror occupies the center of the composition. A gray house with large sections of missing stucco, surrounded by a dilapidated fence, runs off the right side of the picture frame. Tall trees dominate the background.

What makes this image different from the others in Helmbrechts walk is the visual presence of Silas herself reflected in the mirror. None of her individual features are distinguishable, but her bright yellow top contrasts starkly with the white building in front of which she stands, photographing her reflection in the mirror. The image is juxtaposed with the epilogue text, quoted in part here: “Halina Kleiner walked from Helmbrechts to just short of Prachatice in the spring of 1945. I met her in 1998. . . . She remembers a great deal about her experiences. She remembers the biting cold. She remembers the harshness of the guards. She remembers her friends. To my question about what things looked like—“you mean the scenery” she asked—she didn’t have a visual memory of the landscape or her immediate surroundings. . . .22 Kleiner’s lack of visual memory is the result of the dissociation that allowed her to survive. In contrast, although Silas could not see the interior of the Zwodau bunker, she was acutely aware of the details of the environs between Helmbrechts and Prachatice. Kleiner’s story therefore stresses the distinction between first-generation trauma survivors and latter-generation survivors. Like the self-portrait in which Silas’s reflection is distorted by, and made visible solely through, the mirror, Silas can only experience the Helmbrechts death march in an altered, mediated form. Thus, the mirror is a metaphor for her subject position. While her knowledge of the Holocaust has been constructed by historical insight and reflection, her own journey through the German and Czech landscape, and her photographic and written documentation provide Silas with direct experience that the mirror testifies to as proof that an American-Hungarian Jewish woman not only witnessed, but also occupied this historically significant landscape in the present.

The Artist’s Book

Helmbrechts walk functions also as an artist’s book, a highly structured, yet open, container provoking viewers to identify themselves as secondary witnesses to ongoing global atrocities. The electronic version is composed of twenty-two pairs of landscape photographs, corresponding to Silas’s twenty-two days of walking. The self-portrait and epilogue text described above complete the portfolio (see Fig. 3). Viewers can move forward and backwards between the images by clicking on the arrows at the bottom of the screen. The text that corresponds to each day of Silas’s journey becomes visible only when viewers move the computer mouse over the right-hand image. The words, typed in black on a semi-transparent white background, then slowly fade into view, largely obscuring the right image but leaving the left photograph fully visible. The date and the artist’s starting and ending destinations for the day, along with her corresponding journal entry appear in italics at the top right; the New York Times story is located at the bottom and is not italicized. The difference in font style and the blank space separating the two texts emphasize the difference between Silas’s personal, subjective reflections of her journey and the more objective reports of current news events. The right photograph suddenly reappears when viewers move the mouse to another part of the computer screen. The disruption of the visual documentation of the landscape between Helmbrechts and Prachatice through the subtle appearance and abrupt disappearance of the texts underscores the complicated nature of traumatic memory, as the discussion above illustrates. Moreover, the texts themselves act upon the viewer in distinct ways. To complement the earlier examination of the relationship between the photographs and Silas’s personal meditations, I will now focus on the images and the selected news reports, all of which appeared in The New York Times on the same day the corresponding photographs were taken.

Returning to the second day’s photographs (see Fig. 1), neither the exact purpose of the wooden watchtower in the right-hand image nor its date of construction is known. Is it a remnant from World War II? Did Nazis stand guard inside, watching the women on the death march? Or is it a newer stand used for hunting animals? Regardless, the tower symbolizes violence perpetrated by humans against humans, and the way in which dominant hegemonic powers, usually of the state, tend to categorize groups of people considered “others” as animal-like in order to justify their extermination. The news story that Silas paired with the two images calls attention to this connection:

14 April 1998—A report presented by a former Dutch Foreign Minister to the United Nations Human Rights Commission concluded that 1,500 people had been executed in Iraq by the Government of President Saddam Hussein during the past year. Most were executed for “political reasons.”

This text emphasizes how politically-ordered and -justified murders continue years after the Holocaust. Furthermore, the report reveals how both the execution of Iraqis in 1997 and the 1945 death march had to be witnessed and testified to ex post facto by outsiders (the former Dutch Foreign Minister and Silas, respectively) neither of whom personally experienced or witnessed the actual events. This belated testimony underscores the difficulty and/or impossibility of trauma victims testifying to the source of their own traumatic experiences, and the concomitant need for a witness.23 That Silas followed the historically accurate route and subsequently interviewed survivors of the Helmbrechts death march emphasizes her construction of the role of a witness not only to the past but also speaks to her journey and to the genocide, torture, dislocation, and murder that continue to occur and reoccur subsequent to the Holocaust, and to which she calls the public to witness through the inclusion of current events, removed from the larger context of the newspaper.

Antecedents

Silas’ attempt to construct viewers’ memories links her work to a neglected period of 1970s art history when numerous artists throughout the world practiced a kind of sociological art, itself evolved from conceptual and performance art. Groupe de l’art sociologique comes immediately to mind. Formed in Paris by French artists Hervé Fischer and Fred Forest, together with sociologist Jean-Paul Thenot, a 1978 project by Fischer in the central Jordaan district of Amsterdam offers an excellent example. Fischer gained the consent of Het Parool, the local newspaper, to give him a blank page every day for a week, which he then offered to the public to write and design each day. Fischer aimed to “alert the public to how individuals might create their own histories and simultaneously intervene directly in the one-way control of information established by the public media.”24 Ironically, the project revealed that it was artists who had rehabilitated buildings of the Jordaan district, only to be followed by real estate speculators who then bought the buildings and raised rents. The inhabitants— mostly the elderly—were being pushed out of their homes.

Another example of the interrogation of memory and its relation to the history of property and public life is British artist Stuart Brisley’s project, “History Within Living Memory” in Peterlee, England, a township founded in 1948. Brisley, who belonged to Artist Placement Group (APG), set up a bureau in Peterlee and invited townspeople to collect photographs and record memories of the area from before World War I up to the present, documenting and thereby recovering memories, before, during, and after Peterlee transformed from individual villages into a modern city conglomerate.25 The project actively engaged the public in reviving the memory of those villages and stressed the relationship between verbal and visual history and memory.

During this same period, artist and art historian Kristine Stiles created 27.4.1977–26.4.1978: Questions, a work consisting of a year of photographs and texts clipped each day from the San Francisco Chronicle, placed on each side of a board and dated, assembled by month, and exhibited on twelve separate desks, along with a tape recorder instructing viewers to record “autobiographical memories . . . prompted by any of the photographs or texts on these boards.” Hundreds of visitors obliged, confirming the three questions Stiles asked herself when initiating the year-long project: “1) How is our private, autobiographical memory affected by our public life in an international media culture?; 2) How do we experience time in this public/private memory?; 3) Is it possible to reduce art to the state of an empty container open to be filled with content (memory) by individual, private experience?”26 Nineteen years later, Stan Douglas would create Nu.tka, 1996, a video depicting the contemporary landscape of Vancouver Island overlaid with spoken narratives read from eighteenth-century diaries of English and Spanish colonizers of the island. Douglas anticipated Silas’s Helmbrechts walk by collapsing the temporal separation between the traumatic past and the present such that viewers are required to reckon with the juxtaposition of disparate but related visual and textual information, and to integrate history and memory of both site and experience.

Conclusion

While such works may be unknown to Silas, Helmbrechts walk belongs to this larger art historical context.27 The difference between Silas’s work and the aforementioned artists’, however, is her emphasis on the relationship between identity and witnessing. Moreover, Helmbrechts walk can also be understood as the memorialization of a specific moment in time and space (the death march from Helmbrechts, Germany to Prachatice, Czech Republic, from April 13 to May 4, 1945). The photographs that Silas took in 1998 for Helmbrechts walk visually document the landscape through which the women in 1945 anonymously passed and in which many died. Silas’s artist’s book is not, however, an inert archive of images. Rather, the significance of Helmbrechts walk extends beyond the specific context of the Holocaust to the present moment by highlighting contemporary acts of violence. As with the sociological art antecedents cited above, viewers must actively engage with Silas’s art in order to complete the work, filling it as an empty container, as Stiles theorized, with their own thoughts, memories, and experiences. Viewers are asked to consider how history, identity, politics, and the media are intimately intertwined and continuously constructed and reenacted. Such art can bring about heightened consciousness of political and cultural conditions and ideally instigate the need for social change that continuous wars and their concomitant destruction make ever more urgent.

Note: Montage articles, and the images contained therein, are for educational use only.

- The title for my paper derives from a statement by Susan Silas in response to my questions about the significance of the texts she chose for Helmbrechts walk, 1998–2003. Susan Silas, e-mail to author, February 24, 2009. I would like to thank Dr. Kristine Stiles for her support and guidance and artist Susan Silas for generously replying to my numerous questions.

- Silas was unable to complete one ninekilometer section because it did not exist on the contemporary map of the Czech Republic. When Silas and her assistant, Rebecca, came upon what they believed was this “missing” stretch, an older couple discouraged the two from continuing on, concerned that Silas and Rebecca could be in danger if they ventured onto what the home owners considered private property. Silas, “Helmbrechts walk, 1998–2003—meditations,” n.p.; also, Silas, e-mail to author, April 12, 2009.

- The exact number of marchers and deaths is uncertain. According to Silas, approximately 600 marchers began the march from Helmbrechts on April 13, 1945. Ninety-five women died on the way to Prachatice and all are buried in Volary, Czech Republic. Silas’s figures are based on the transcript from the 1969 trial of former Helmbrechts camp commander Alois Dörr. She also photographed every headstone in the Volary cemetery. Silas, e-mail to author, April 12, 2009. In contrast, art historian Dora Apel used the data published in Daniel Goldhagen’s controversial book, Hitler’s Willing Executioners (1997), writing that the Helmbrechts death march started with 580 Jewish prisoners, 590 non- Jewish prisoners, and 47 guards. Officially, 178 marchers died; unofficially 275 died. Apel, Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnessing (New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 140.

- Silas, “Helmbrechts walk, 1998–2003— meditations,” n.p.

- Ibid.; also, Silas, e-mail to author, April 12, 2009.

- I have not seen the video. Apel, Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnessing, 139; also, Susan Silas, e-mail message to author, February 24, 2009.

- The electronic version of the artist’s book 1998–2003, http://www.susansilas.com/portfolio/helmbre chts.html.

- Silas, e-mail to author, February 24, 2009.

- Nanette C. Auerhahn and Dori Laub, “Intergenerational Memory of the Holocaust,” in International Handbook of Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma, ed. Yael Danieli (New York: Plenum Press, 1998), 22; 37.

- Brett Ashley Kaplan, “Susan Silas: On ‘Helmbrechts walk,’” Camera Austria International 98 (2007): 39.

- Dori Laub, “An Event Without a Witness,” in Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History, ed. Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub (New York and London: Routledge, 1992), 80.

- Ibid.

- Kaplan, “Susan Silas: On ‘Helmbrechts walk,’” 39.

- Silas, e-mail to author, February 24, 2009.

- Susan Silas, “Day 2,” Helmbrechts walk, 1998–2003, http://www.susansilas.com/portfolio/helmbre chts.html.

- Kaplan, “Susan Silas: On ‘Helmbrechts walk,’” 39.

- Ibid., 49.

- For more about Silas’s We’re Not Out of the Woods Yet, see Apel, Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnessing, 132–34. For Kiefer’s Occupations series, which is formally entitled Anselm Kiefer/ Zwischen Sommer und Herbst 1969 habe ich die Schweiz, Frankreich und Italien besetzt (Anselm Kiefer/between summer and fall 1969 I occupied Switzerland, France, and Italy), see for example, Daniel Arasse, Anselm Kiefer (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001); Andreas Huyssen, “Anselm Kiefer: The Terror of History, the Temptation of Myth,” October 48 (Spring 1989); Brett Ashley Kaplan, Unwanted Beauty: Aesthetic Pleasure in Holocaust Representation (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007); Christine Mehring, “Continental Schrift: The Story of Interfunktionen,” ArtForum (May 2004); Lisa Saltzman, Anselm Kiefer and Art after Auschwitz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

- Rebecca was a graduate student who accompanied Silas on her journey from a distance in a car while Silas walked. Silas felt this was necessary for her own safety. Silas, e-mail to author, February 24, 2009. The quotation is from Silas, “Day 6,” Helmbrechts walk, 1998–2003, http://www.susansilas.com/portfolio/helmbre chts.html.

- Cathy Caruth, “Introduction” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory, ed. Cathy Caruth (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 4.

- The author in discussion about the etiology of trauma with Kristine Stiles, April 11, 2009.

- Silas, “Epilogue,” Helmbrechts walk, http://www.susansilas.com/portfolio/helmbrechts.html.

- According to Laub, with regard to the Holocaust, it was “the very circumstance of being inside the event that made unthinkable the very notion that a witness could exist, that is someone who could step outside of the coercively totalitarian and dehumanizing frame of reference in which the event was taking place, and provide an independent frame of reference through which the event could be observed.” The failure to be a witness at the time of the event, Laub argues, was a problem of the victims, perpetrators, and bystanders alike. Laub, “An Event Without a Witness,” 81. See also, Laub’s “Bearing Witness or the Vicissitudes of Listening,” in Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History, ed. Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub (New York and London: Routledge, 1992), 58. Moreover, as cultural critic Cathy Caruth contends, “the impact of the traumatic event lies precisely in its belatedness.” See Caruth’s “Introduction” in Trauma: Explorations in Memory, ed. Cathy Caruth (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 3–12.

- Kristine Stiles, “Concerning Public Art and ‘Messianic Time’” (1998), n.p., http://www.perjovschi.ro/files/dan%20Mesiani c%20Time.doc (accessed March 19, 2009).

- APG was founded in 1966 by John Latham to place artists in public institutions where they might change decision-making processes. Latham’s goal was to create a way for the neglected creative resources of artists to gain a greater impact in changing society. Stuart Brisley was appointed artist-inresidence to Peterlee in 1976. For further information about the “History in Living Memory” project, see Durham City Council, “People past and present archive,” Durham City Council, http://www.durham.gov.uk/Pages/Service.asp x?ServiceId=6614 (accessed March 19, 2009).

- See Kristine Stiles, Questions, 1977–1982 (San Francisco: KronOscope Press, 1982).

- Silas has cited Bruce Chatwin’s What Am I Doing Here and Werner Herzog’s Of Walking in Ice: Munich-Paris 11/23 to 12/14, 1974 as influences in terms of thinking about the metaphor of journey and the significance of her daily writings. She has also noted how Albert Speer ritually walked the Berlin prison garden path he designed while imprisoned there. Speer tracked how far in kilometers he traveled and imagined that he was actually walking around the world. See Silas, “Helmbrechts walk, 1998–2003—meditations.”

Published in Montage, 2009